This book excerpt is adapted from World-Class Brain: The Edge that Helps Peak Performers Succeed and How You Can Develop It, by Dr. Harald S. Harung, researcher on leadership and performance, and Dr. Frederick Travis, neuroscientist.

The brains of world-class performers are different from the brains of average performers. No surprise there. But what is surprising is that regardless of whether these top performers are athletes, musicians, or CEOs, their brains share one feature that makes them stand out: More integrated functioning. A world-class brain works in a more coherent, relaxed, wakeful, and efficient way.

Our short, readable book debunks the assumptions that age, work experience, education, practice, and incentives underlie high performance. Research shows that these factors have only a small influence on exceptional performance—for example, education accounts for only 1 percent of performance levels, work experience only 3 percent, and age in adults 0 percent.1,2

Instead, we found that the level of brain integration is the key for high performance in diverse areas of life. World-Class Brain tells the story of top performers and the unique style of brain functioning they share, leading to greater levels of happiness, peak performance, and a more highly developed moral sensibility.

This multifaceted story includes the importance of lifestyle in gene expression and neuroplasticity—a mechanism whereby lifelong brain refinement can be achieved. Here we’ll show how sleep, physical exercise, playing and listening to music, and, in particular, transcending through the Transcendental Meditation (TM) technique are the keys to mind-brain development.

A world-class brain works in a more coherent, relaxed, wakeful, and efficient way.

The Key to Peak Performance: Brain Integration

In our research, we have found that the key to peak performance is something called integrated brain functioning. This is measured by EEG (electroencephalogram), a test used to evaluate the electrical activity through which brain cells communicate.

What this means is that the top-performing brain tends to be more coherent. The various parts of the brain, each of which has different responsibilities, are collaborating in a better way—like the musicians of an orchestra working in concert to create beautiful music rather than just tuning up in a cacophony of noise.

The brain with higher integration is also more relaxed and wakeful, and more efficient (using less energy to perform a task).

For research purposes, we combined these three different measures—brain coherence, relaxed wakefulness (alpha1 brain waves), and brain efficiency—to create the Brain Integration Scale.3

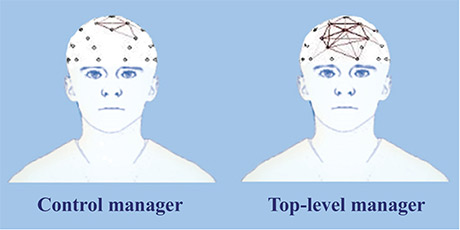

Brain Coherence Maps show stronger coherence in top-level managers compared to low-level or “control” managers. Lines between points indicate 70% coherence; darker lines indicate stronger coherence.

In our research, world-class performers in sports and business scored substantially higher on the Brain Integration Scale than controls: 33 world-class athletes had higher levels of brain integration compared to 33 average athletes;4 and 20 top-level managers had greater brain integration compared to 20 low-level managers.5

For example, the figure comparing Brain Coherence Maps shows the brain wave coherence between various areas of the frontal cortex in a typical low-level or “control” manager compared to a typical top-level manager in our research. When there is a line between two points, this means that the brain waves at those points are at least 70 percent in coherence with each other; the darker the line, the stronger the coherence.

The results from our study of classical musicians were unexpected. We found that the 25 professional classical musicians had high levels of brain integration, but the brain integration scores of the 25 amateur classical musicians were almost as high.6 This may have resulted from the fact that if you play music from childhood, which both the professional and amateur musicians had, your brain is more integrated as an adult.

The top-performing brain is more coherent. The various parts of the brain, each of which has different responsibilities, are collaborating in a better way—like the musicians of an orchestra working in concert. The brain is also more relaxed and wakeful, and more efficient.

Mind-Brain Development = Nature + Nurture

Are some people simply born with a more integrated brain and therefore are spontaneously able to be world-class performers? Or do world-class performers, by virtue of their diligent practice and performance, develop a more integrated brain, which then allows them to excel? In other words, is it due to nature or nurture?

Our research leads us to believe that both play a role. We are born with strengths and preferences; our life experiences shape our innate abilities into who we are at any moment. Our present level of mind-brain development depends on the interaction of both.

• Nature consists of our genetic endowment, including each individual’s physical and mental traits, tendencies, and talents; and the natural tendency to grow towards higher states of human development, which we all share.

• Nurture consists of the sum of our experiences in life: family experiences, social experiences in school and with friends; the choices we make for different lifestyles, different vocations, and different paths in life; even the society and time we are born into.

Our diet, ongoing experience, and the level of stress or harmony in our life add “tags” to our DNA. These tags influence genetic expression, leading to reduced immune functioning and greater illness, or to good health, happiness, and a long life. These tags are part of epigenetics, which literally means “above the gene.”

We are born with strengths and preferences; our life experiences shape our innate abilities into who we are at any moment.

How the Brain of a Taxi Driver Changes with Experience

Neuroplasticity is a hot area of research today. For example, a four-year study examined brain connections in London taxi drivers.7 The research investigated the size of the hippocampus, the part of our brain that is engaged in memory, including spatial navigation.

To become licensed as a taxi driver in this huge city, you have to build up extensive knowledge about the quickest route from one place to another, essentially outperforming the GPS. The study involved 41 men who trained for their license and passed the test, 38 who started training but dropped out or didn’t pass, and 31 non–taxi drivers who served as controls.

At pretest, brain scans using fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) found no differences between the three groups. But at post-test, the rear part of the hippocampus had grown to become significantly larger in the taxi drivers who had become licensed, while there was no change for the other two groups.

At post-test, the rear part of the hippocampus had grown to become significantly larger in the taxi drivers who had become licensed.

4 Ways to Harness Neuroplasticity and Develop Brain Integration

Research suggests four complementary experiences that contribute to higher brain integration throughout life: sleep, exercise, music and visual arts, and practicing the TM technique. The key point is that sleep and exercise allow us to use our current resources while transcending helps us to develop greater resources. Of course, a healthy diet is also good for the brain, but that is outside the scope of this book.

1. The Value of a Good Night’s Sleep

Why do we sleep? Why do we spend a third of our life with our eyes closed and not being productive? Actually, we are being productive. Sleep is removing the effects of being awake.

During activity, according to recent research published in Science, the brain uses and re-uses neurotransmitters and proteins to register changing experiences.8 With constant use, these particles break down, producing what is called sleep dirt. We make 7 grams of sleep dirt a day—which would fill a teaspoon. This sleep dirt contains some metabolites that are inert, as well as neurotoxins and amyloid, which is associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

During the deepest phases of sleep, the supporting cells around the neurons constrict, thereby generating 60 percent or more greater space around the neuron. This space pulls the fluids around the neuron to pass over the neuron and wash out the sleep dirt. In other words, sleep gives the brain a bath.

If you do not get sufficient amounts of sleep (7–8 hours a night), the sleep dirt builds up, leading to problems in emotional regulation, memory, and decision making. Two thirds of adults do not get sufficient sleep and have accumulated sleep dirt. Thus, most people are not able to use their full mental capacity.

Sleep deprivation reduces learning, impairs cognitive functioning,9 and is tied to the onset of dementia.10 In addition, as you get more tired throughout the day, the first part of your brain to slow down is the frontal cortex, which is the CEO of the brain. When you’re tired it goes offline, and you become more emotional and less able to see the big picture.

Thus sleep is critical for a healthy mind and body and a high level of performance.

Sleep is critical for a healthy mind and body and a high level of performance.

2. Adequate Exercise

Exercise is critical for optimal health. When you exercise, you increase blood flow to the brain, you produce new neurons in the memory centers of the brain (the hippocampus), and you produce a compound that facilitates laying down memories (brain-derived neurotrophic factor, or BDNF).

Students who exercise do better academically and on standardized tests of intelligence. They are happier and more resilient. Higher fitness is also tied to faster brain processing of information. The more times a student can run around a track is positively and significantly correlated with higher performance on standardized academic tests such as the SAT or GRE.11

In short, exercise can help you use your full cognitive resources. The more physically fit you are, the better you can withstand stress.

Why is this the case? When you exercise four things happen:

• Cardiovascular functioning improves, so you can do more work without getting tired and feeling stressed.

• More oxygen reaches your body and brain because the heart beats faster.

• More new brain cells are produced in the hippocampus when you exercise.

• There’s an increase in the neural growth protein BDNF, which supports neuroplasticity.

So exercising enriches the brain with oxygen, primes the memory centers of the brain, facilitates neural changes to enhance memory, and opens up the possibility of brain refinement. Research shows that sufficient exercise throughout life is also important for good physical and mental health and well-being, which provides the basis for our performance.12,13

More new brain cells are produced in the hippocampus when you exercise.

3. Enjoying Music and Engaging in the Arts

The arts are important. While math and language develop localized brain circuits, musical training facilitates more holistic brain development: It increases connections between the left and right hemispheres, since you need to focus on the specific notes and how to play them at the same time that you maintain attention on the longer melody line.

Playing an instrument is reported to lead to extensive changes in brain functioning.14,15 It supports the ability to distinguish a tone from background noise and develops brain areas relevant to remembering a score, timing issues, and coordination with other musicians. In addition, musical training is reported to strengthen connections between auditory and motor regions while activating brain areas that put everything together.

Although playing music probably gives the largest benefits, there are also benefits from listening to music. One study found that brain connectivity was highest when people listen to their preferred music, such as country versus classical.16 Research at the University of Arts in London concluded that secondary education students who learn about art and culture achieve better grades in all disciplines.17

Musical training facilitates more holistic brain development: It increases connections between the left and right hemispheres.

4. Transcending with the TM Technique

There is a wide range of meditation techniques available today that differ in the amount of control used during the practice. As explained below, different meditation techniques lead to distinctly different brain wave patterns and subjective experiences.18,19,20

• Focused attention, such as Zen meditation, require the most effort. Meditations in this category may focus on one part of the body, the breath, or a compassionate mood. Whenever you focus attention, faster gamma brain waves (30–50 Hz) dominate in the brain.

• Open monitoring requires less control. During open monitoring practices, such as mindfulness meditation, you dispassionately observe internal processes, such the breath, bodily states, thoughts, or feelings that may arise. This results in frontal theta brain waves (5–8 Hz) and alpha2 brain waves (10–12 Hz) towards the upper back (parietal lobe) of the brain, indicating that one is following inner mental processes.

• Automatic self-transcending requires the least amount of control. In the effortless practice of the TM technique, one learns how to transcend systematically. The word automatic is important: Any focusing or control of the mind leads to localized brain activity and does not allow the mind to settle down to inner silence.

The TM technique allows one’s mind to settle down from active thinking to inner wakefulness, free from thought. Whereas during focused attention and open monitoring, one maintains mental activity, in the practice of the TM technique, one transcends mental activity. EEG measurements during the TM technique show alpha1 (8–10 Hz) brain waves in the front of the brain, indicating that the attention is awake, but inner-directed.

A new study confirms that the TM technique leads to a distinctive state of rest and wakefulness that is not found in other meditations.21 The fMRI patterns of 16 subjects during their TM practice found that there was increased activity in the areas of the prefrontal cortex related to attention—indicating alertness, as in practices involving focused attention or open monitoring. However, unlike those procedures, during the TM technique there was also decreased activity in the areas related to mental stimulation, indicating deep rest.

Transcending Is Key to Brain Integration

Recall our finding that high performers tend to have high brain integration. Research on the Transcendental Meditation technique shows that transcending leads to higher levels of brain integration.22 In fact, regular practice of the TM technique develops all three aspects of the Brain Integration Scale: coherence, relaxation and wakefulness, and efficiency.

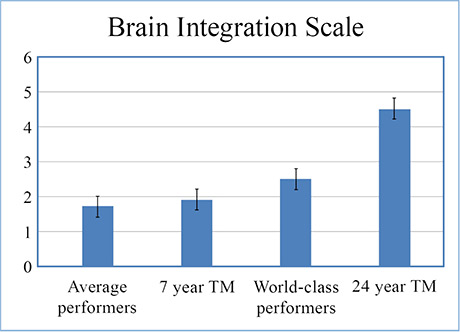

Levels of brain integration in 4 groups. This figure shows the Brain Integration Scale scores of average performers; individuals with short-term TM practice (7 years); world-class athletes, managers, and musicians; and individuals with long-term TM practice (24 years).

This figure presents the brain integration for four groups of subjects, all of whom were at least 25 years of age: average performers in our database, including the controls of our three world-class performance studies; individuals with short-term TM practice (7 years); the world-class performers (athletes, managers, and musicians) that we studied; and individuals with long-term TM practice (24 years).

We found that long-term practice of the TM technique is associated with brain integration far beyond that of the top performers in our three studies.

Notice in the figure that the top-level performers have Brain Integration Scale scores a little higher than the short-term TM group, but only about half that of the long-term TM group.

Obviously, many factors contribute to high levels of brain integration in the peak performers. However, the data suggest that adding transcending to one’s daily routine could enhance brain integration, leading to enhanced performance.

Top-level performers have Brain Integration Scale scores a little higher than the short-term TM group, but only about half that of the long-term TM group.

Brain Changes during TM Practice Carry into Activity

Right from the very early days of TM practice, the brain shows increased frontal alpha1 coherence during meditation. This brain signature signals that the mind is at its ground state—silent and awake. In fact, during meditation, high levels of alpha1 coherence are already seen after just a few months of TM practice.

EEG coherence for 4-month and 8-year meditators. During TM practice (upper part) there is little difference between a 4-month and an 8-year meditator, but outside of meditation (lower part), the difference in brain coherence is much larger.

Thereafter, what changes with regular, twice-daily TM practice is that the inner experience and the brain signature of inner wakefulness become integrated with daily activity. As one meditates regularly month after month, year after year, this alpha1 coherence is increasingly present outside of meditation, providing an enhanced basis for processing experience.

This is illustrated in this figure. The upper part shows the alpha1 coherence during the TM technique of a person who had been meditating four months (left) compared to a person who had been meditating for eight years (right). The coherence is very similar.

This is because TM practice is effortless, using the natural tendency of the mind to transcend. Additional practice does not make a natural process go any better.

The lower part of this figure presents a comparison of the same two people with their eyes open during a challenging computer task. The person on the right, who has been meditating for eight years, shows the same brain coherence as during TM, even with his eyes open and engaged in a task. In contrast, the brain of the person meditating for only four months has much less alpha1 coherence during activity.

What changes with regular, twice-daily TM practice is that the inner experience and the brain signature of inner wakefulness become integrated with daily activity.

Nature, Nurture, and the Lifelong Gift of Neuroplasticity

Due to neuroplasticity, our brain changes and develops depending on how we use it. This suggests that the world-class performers we studied had integrated brains because of both nature—their genetic endowment—and their ongoing life experience. And in turn, having an integrated brain facilitated their performance, just as developing better mind-body coordination facilitates performance in all sports and in playing all types of music.

Neuroplasticity takes place throughout life. It is part of the mechanism that facilitates mind-brain development in adults. The choices we make lead to specific experiences, which strengthen specific brain circuits. Our ongoing life experiences strengthen specific brain circuits, shape our stress response, and even shape expression of our genetic code.

Learn more. Order World-Class Brain here ►

Our ongoing life experiences strengthen specific brain circuits, shape our stress response, and even shape expression of our genetic code.

About the Authors

For a more comprehensive treatment of our research, see our book, published by Routledge, Excellence through Mind-Brain Development: The Secrets of World-Class Performers (2016), which may be ordered at Amazon.com.

Harald S. Harung, Ph.D.

Harald S. Harung, Ph.D., is an interdisciplinary researcher with a focus on peak performance and leadership, and is himself a high performer in lecturing, writing, and the sport of orienteering. He holds a Ph.D. from the University of Manchester and has been a researcher at Oxford University, a naval officer, the CEO of an engineering company, and president of an international business college.

For many years Dr. Harung has been teaching “Leadership, Ethics, and World-Class Performance” to classes of up to 500 students at Oslo Metropolitan University. He has been working as a researcher and consultant on peak performance for more than 30 years, both for individuals and organizations. He has published 37 papers and 5 books, and lectures worldwide. For more information, visit his website at https://harvest.no.

Frederick Travis, Ph.D.

Frederick Travis, Ph.D., has been Director of the Center for Brain, Consciousness, and Cognition at Maharishi International University (MIU, formerly Maharishi University of Management) since 1990. His work has focused on brain development from birth to adulthood, higher states of consciousness, and the effects of meditation experiences on the brain.

Dr. Travis has published 78 papers and 4 books. He teaches at the undergraduate, master’s, and doctoral levels and lectures globally on the brain and consciousness. Recently, the New York Academy of Sciences invited him to present his research. To better understand excellence, he has researched the brain patterns of successful people with Dr. Harung. For information, visit Dr. Travis’ web page at MIU.

I play the flute, mandolin and guitar and piano for 12 years when young, have done TM for 6 years faithfully and other forms of meditation and mindfulness since 1974 in order to help with schizophrenia. I don’t seem to notice much improvement in my brain but I am calmer, less tempermental and have functioned in society healthfully all this time, holding down a demanding job as an international FA until 2003 when I retired from sheer exhaustion. Thought you might find this useful or interesting, especially the part about paranoid schizophrenia. Love TM.

Thank you, Betsy, for sharing your inspiring story! You have used music and meditation and now the TM technique to great effect in your life. Thanks again, and enjoy your much-deserved retirement!