Matthew Beaufort, a specialist in art history and Associate Professor of Humanities at Maharishi University of Management (MUM), explores the sculpture of Michelangelo in terms of how it resonates with our practice of the Transcendental Meditation® (TM®) technique. To experience these works of art and many others in person, enjoy Professor Beaufort’s MUM Tour of Italy, May 2020, (CANCELLED due to COVID-19 travel restrictions worldwide.) with sightseeing, spiritual sites, and delicious Italian food. Celebrate the art of living with other TM Meditators and friends! People who do not practice the TM technique are welcome as well.

Astonishing! Awe-inspiring! Mesmerizing! These are typical responses to Michelangelo’s David when people experience it at the Accademia Gallery in Florence, Italy. What creates these feelings? The marble statue’s monumental size, at 18 feet? The technical virtuosity of the carving? Michelangelo’s psychologically intense interpretation of a teenager slaying the giant Goliath? All of the above.

Michelangelo’s sculptures also embody universal principles of consciousness that energize our awareness. These principles of consciousness, as explained by TM Founder Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, can inspire us to develop greater creativity and success in our own lives.

Michelangelo’s sculptures also embody universal principles of consciousness that energize our awareness… [and] can inspire us to experience and achieve greater creativity and success in our own lives.

The Story of David and Goliath

Many Renaissance artists chose to depict the archetypal story of David and Goliath, from the book of Samuel in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. The Israelites are forced to battle the Philistines, who send out the mighty giant Goliath. He challenges them to offer their best warrior for one-on-one combat.

Only David, a shepherd boy without sword or shield, is courageous enough to answer the call. What David has is the power of righteousness. He feels strongly that God will aid him. David puts a stone in his sling and hurls it into Goliath’s forehead, which stuns the giant. David then takes Goliath’s own sword and cuts off his head.

Michelangelo’s Unique Interpretation of David

Michelangelo’s David (1501–03), torso

Michelangelo’s David (1501–03) was unprecedented in the history of art, since previous portrayals of David often drew upon ancient classical statues for ideal proportions.

Michelangelo’s David, the first nude to be carved on a colossal scale since antiquity, was boldly unclassical. For example, the hands, feet, and head are too big in proportion to the body. Michelangelo emphasized the hands because they will slay Goliath. He enlarged the head to intensify the psychological impact and so that it can be seen readily by viewers far below.

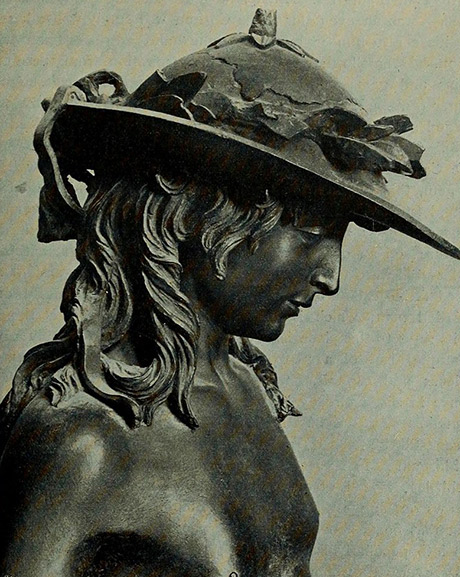

Previous statues showed David at the moment of triumph: He stands with sword in hand, having beheaded Goliath. In 1428, for example, Donatello’s David, now in the Bargello National Museum in Florence, was cast life-size, in gleaming bronze. This David, with its sleek lines and smooth surfaces, is sensuous and graceful. Sporting a stylish hat, he seems more like a dandy than a warrior.

Donatello’s David (ca. 1428), upper torso

We can admire Donatello’s David for his elegant refinement, but he seems detached from the action, uninvolved, as if he is daydreaming.

Michelangelo’s David, on the other hand, is fully engaged. His neck strains and his brows knit as he defiantly sizes up his opponent with heroic determination.

He is shown at the moment before he acts. His right hand clutches the stone. His veins and muscles swell as he prepares to attack. His eyes bulge with a fearless, penetrating gaze. He is outwardly calm yet inwardly alert.

In his stance and in his countenance, this David expresses extraordinary pent-up energy—the potential to act forcefully and successfully.

Michelangelo’s David… is shown at the moment before he acts… He is outwardly calm yet inwardly alert.

David’s Mind-Body State: Rest Is the Basis of Activity

The state of mind and body represented in Michelangelo’s David may remind us of aspects of our experience during the TM technique. During our TM practice we settle down to a state of deep calm, yet we are inwardly alert, in a state of heightened awareness. Unlike the David, our eyes are closed and our attention is within.

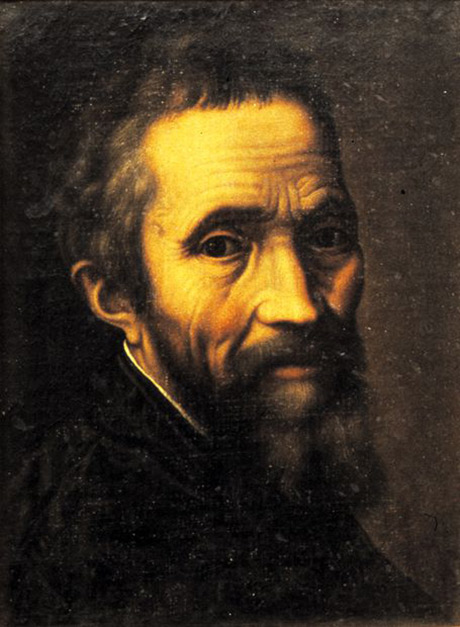

Portrait of Michelangelo by Marcello Venusti (ca. post-1535), oil on canvas, Casa Buonarroti, Florence

Experiencing this state of restful alertness recharges us mentally and physically, so we can express more of our latent potential. We emerge with the ability to act energetically to meet the needs of the moment.

Maharishi used the analogy of the bow and arrow to describe the value of the TM technique as a preparation for dynamic activity. When we want an arrow to fly far and true, we pull back the arrow as far as we can on the bow. There, it is momentarily in a state of rest, but with the inherent dynamism of potential energy, which allows it to fly with great force when we release it.

Practicing the TM technique is like pulling the arrow of our awareness back on the bow, so when we come out of meditation, we can hit the target we seek to achieve. Another way to say this is that rest is the basis of activity, one of the basic life principles Maharishi also spoke about. The profound rest gained during our TM practice is the basis of dynamic and fulfilling action.

Practicing the TM technique is like pulling the arrow of our awareness back on the bow, so when we come out of meditation, we can hit the target we seek to achieve.

Michelangelo’s David is shown at the moment when he has pulled the arrow far back on the bow. He is now poised to plunge into heroic action.

Michelangelo’s Inner Artistic Vision: Knowledge Is Structured in Consciousness

When Michelangelo was awarded the commission for David, he was given a huge block of stone that had been abandoned by another sculptor as unsuitable. But Michelangelo saw what others could not see. He was able to envision in that block the magnificent form that was to become his now famous David.

Michelangelo’s Saint Matthew (1503–05), unfinished

Maharishi commented on Michelangelo’s creative process and its implications for consciousness:

“You remember that the very great and beautiful artist Michelangelo said that he was merely scraping out or exposing the figure that already existed in the piece of marble… Where was that figure structured? Certainly it existed in the marble, but it was a copy of the structure of the consciousness of the artist. The artist comprehends the outlines of the figure—maybe a long face or a short nose—in his consciousness, and then he wants to depict it on marble, on paper, on clay, or on wood, but he carves the wood to match the picture he contains in his awareness.”1

In other words, Michelangelo first structured his art in his consciousness, then manifested it in stone or paint.

Maharishi used the example of Michelangelo’s creative process to highlight the principle that knowledge is structured in consciousness. This principle means that the quality and content of the knowledge a person gains depends on the clarity of his or her consciousness.

For example, if we are drowsy, we can only gain incomplete and unsatisfying knowledge. But if we are alert and aware, knowledge can be more complete and fulfilling. The quality of knowledge we gain is crucial for success in life, because, as Maharishi pointed out with another principle, knowledge is the basis of action.2

“Where was that figure structured? Certainly it existed in the marble, but it was a copy of the structure of the consciousness of the artist.” —Maharishi

Michelangelo’s Creative Process—Form Emerging from the Formless

By looking at a series of Michelangelo’s unfinished life-size sculptures, also in the Florence Accademia, we can see his creative process of manifesting the unseen from an uncarved block.

Michelangelo’s The Waking Slave (ca. 1530–34), unfinished

In the Waking Slave (ca. 1530–34) we see a figure beginning to emerge from the marble, as Michelangelo cuts away the stone. The formless begins to take form. But the hands and feet, so vital in David, are not yet defined in this work. The Waking Slave appears to struggle to free himself from the stone, as one sometimes struggles to wake up from a deep sleep.

This statue suggests Michelangelo’s belief that the soul was imprisoned in the body and sought to free itself from the limitations of physicality and matter. His thinking was strongly influenced by the Neo-Platonism of the Renaissance, in which the transcendental ideas of the ancient Greek philosopher Plato were reborn.

The statue of Saint Matthew (1503–05, shown earlier) is somewhat more defined than the Waking Slave in certain areas, such as the face, the left leg that thrusts out, and the folds of clothing. However, there is still a strong sense of form emerging from the formless marble. Michelangelo compelled the figure to come forth by carving it out of the block of stone while looking at it from the main frontal angle.

The Bearded Slave (1530–34, not shown) is a more finished sculpture, with most of the body now freed from the marble. The details of the face are well defined, yet the hands and one foot are still not visible. The formless has almost fully expressed itself in form.

Maharishi describes this creative process as a source of joy for the artist: “All these strokes of the artist—all his movements, all his activity—move in accordance with what he holds on the level of his awareness. The ability to portray exactly that image is the skill of art, so the basis of the artist is wide and detailed comprehension. This ability to comprehend precisely, and retain that comprehension during the act of expressing it, is the joy of the artist.”3

“This ability to comprehend precisely, and retain that comprehension during the act of expressing it, is the joy of the artist.” —Maharishi

Ideal Forms in Art Draw Us Closer to the Transcendent Source of All Forms

Why did Michelangelo seek to portray an ideal human body? He does so in most of his art, including his paintings on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel and his famous sculpture housed in St. Peter’s Basilica, the Pietà (“the Pity”), in which Mary holds the body of her dead son Jesus.

The Pietà by Michelangelo, St. Peter’s Basilica, the Vatican

Once again, we may find the answer in Neo-Platonism, which posited a single source from which all existence emanated. By going deep within, the individual soul could mystically unite with this source.

Inspired by Neo-Platonism, Michelangelo may have thought that ideal forms in art could lead the soul inward toward the perfect, transcendental forms that structure all of creation. Thus beauty in art could be a gateway to experiencing the transcendental beauty of the soul, which is divine.

This Neo-Platonic view reinforces the value of experiencing great art in person. The experience of beauty can induce transcending to subtler levels of awareness. Beauty can awaken us to the higher possibilities of our consciousness and inspire us to attain them.

Beauty in art could be a gateway to experiencing the transcendental beauty of the soul, which is divine.

Connecting These Universal Principles to Our Lives

Michelangelo’s Moses (1513–15), San Pietro in Vincolo, Rome

We can relate these principles to our own lives, whether we are visual artists or not. We are all artists in the sense that we are all creators. We seek to create something significant in our lives, such as professional success, a harmonious family, or a peaceful community and world.

We can more effortlessly create what we want if our consciousness is clear and expanded. From this depth of awareness we can envision clearly what we seek, and then take the steps to achieve it.

“Here is the need for Transcendental Meditation in the life of an artist,” Maharishi explained. “In order to mold in his consciousness any shape, any detailed form, he must be able to hold it in his awareness, holding it in his awareness even with his eyes open, with hands moving, and with his sense of discrimination active… For this it is necessary that his consciousness is pure and should not have any foreign material in it. For consciousness to be pure, one has to have a stress-free nervous system.”4

The TM Technique Helps Us Live a Creative and Fulfilling Life

The regular practice of the TM technique allows the mind and body to settle down to a state of deep rest, where it can naturally release fatigue and dissolve deep-rooted stresses. Then we can more easily and effectively fulfill our personal and professional aspirations. We can create what we envision in our awareness.

“For consciousness to be pure, one has to have a stress-free nervous system.” —Maharishi

We can look to Maharishi’s example of the successful artist for inspiration: “What is happening when the artist has a figure in his consciousness and he tries to create it? He is expanding his consciousness, and expansion of awareness, being the nature of life, is a joy; it is a wave of life. The artist lives in the waves of expansion, in the waves of evolution, all the time in the waves of growth.”5

We can culture a creative and inspired life through regular practice of the TM technique and its advanced programs. To accelerate your growth, you can learn Advanced Techniques of the TM program and the TM-Sidhi® program, which cultivates the ability to think and act spontaneously from the transcendental field of awareness. For more information on all TM follow-up and advanced programs, visit EnjoyTM.org.

Being with other TM practitioners, such as at Knowledge Meetings, TM Retreats, and other events sponsored by your local TM Center, is also enjoyable and supportive to one’s personal growth. Joining one of MUM’s travel tours is a way to experience the world with the fresh perspective of the Consciousness-Based® approach to knowledge.

We invite you to join us on the MUM Tour of Italy, May 2020! For information, visit tours.mum.edu or write to me at mbeaufort@mum.edu. (CANCELLED due to COVID-19 travel restrictions worldwide.)

For more insights on art and consciousness, see Professor Beaufort’s article on Michelangelo’s paintings in the Sistine Chapel.

For more information about Consciousness-Based education at Maharishi University of Management, visit MUM.edu.

Matthew Beaufort, Associate Professor of Humanities at Maharishi University of Management (MUM), has organized four tours of Italy, as well as trips to France, England, and Spain. He has two masters degrees, studied art history and Italian in Florence, and edited and contributed to the book Consciousness-Based Education and Art: Developing the Infinite Creativity of Every Student (MUM Press, 2012).

Notes

1. Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, SCI and the Role of the Artist (audiotaped conversation, 14 March 1974, Vittel, France). Quoted in “Maharishi’s Principles of Art and Art Education,” by Lee C. Ferguson, Ph.D., in Consciousness-Based Education: A Foundation for Teaching and Learning in the Academic Disciplines, Volume VII: Consciousness-Based Education and Art, Volume Editor: Matthew Beaufort (Consciousness-Based Books, MUM: Fairfield, IA, 2010), p. 235-6.

2. Ibid., p. 236.

3. Ibid., p. 236.

4. Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, “Art: To Articulate Life so that Every Aspect Is Developed to Its Full Glory.” (Videotaped presentation by Michael Cain, professor of art, followed by a lecture by Maharishi; September, 1975, Maharishi International University, Fairfield, IA.) Quoted in “Maharishi’s Principles of Art and Art Education,” by Ferguson, in Consciousness-Based Education, Volume VII, p. 235.

5. Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, SCI and the Role of the Artist. Quoted in “Maharishi’s Principles of Art and Art Education,” by Ferguson, p. 236.

Comments

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Maharishi

The Truth about Creativity and Suffering

Is suffering necessary to create? Maharishi explains the real relationship between creativity and suffering in this talk collected in The Flow of Consciousness: Maharishi Mahesh Yogi on Literature and Language.

Creativity & the Arts

Expand Your Awareness with Great Italian Art—and a Tour of Italy

Discover universal qualities of consciousness in the works of Michelangelo and Raphael in this exploration of two masterpieces of Renaissance art. To experience these art works and many others in person, enjoy the MUM Tour of Italy in May 2020.

Creativity & the Arts

Continuous Creation

Artist Kuno Vollet creates iconic objects with fullness of emptiness at their center. “TM influenced my art from the beginning, because you have to be so relaxed, not tense, when you do your work… I get into a deeper and deeper state, and it’s just a flow, where there is no disturbance. The art is just being created.”

Creativity & the Arts

Achieving the Extraordinary

Contemporary icons speak about TM and creative renewal. “It has given me effortless access to unlimited reserves of energy, creativity, and happiness deep within.” —David Lynch