Do you have a science question for Dr. David Orme-Johnson? Please send your query to editors@enjoytmnews.org. As one of the principal researchers on the Transcendental Meditation® (TM®) technique worldwide, with over 100 publications in peer-reviewed journals, Dr. Orme-Johnson has presented TM research in more than 56 countries to scientific conferences, government officials, and the United Nations.

Question: I read a lot about mindfulness meditation in the news and on the Internet. How does the Transcendental Meditation technique differ from mindfulness?

Dr. Orme-Johnson: Essentially, the goal of all meditation techniques is to have a happy, successful, less stressful, and more fulfilling life—to feel closer to the organizing intelligence of nature, and to get a good night’s sleep!

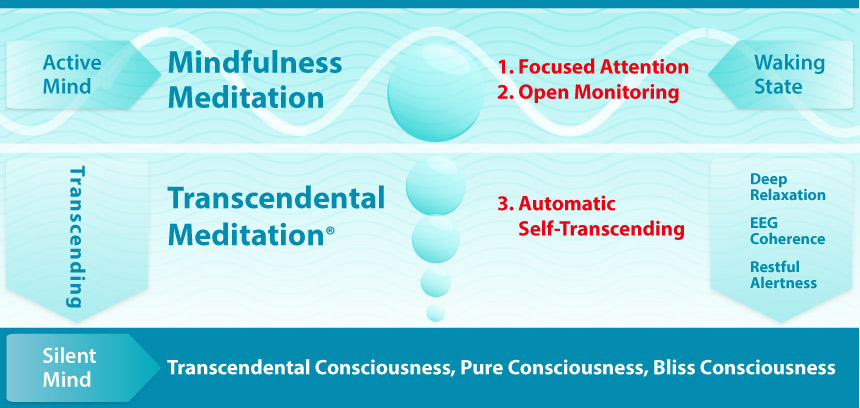

Scientists have identified three basic categories of meditation, which differ in their practice, in their immediate effects on mind and body, and in their outcomes in daily life. These meditative categories are called Focused Attention, Open Monitoring, and Automatic Self-Transcending. Mindfulness involves both Focused Attention and Open Monitoring. The TM technique falls in the category of Automatic Self-Transcending.1 (See chart below.)

Scientists have identified three basic categories of meditation, which differ in their practice, in their immediate effects on mind and body, and in their outcomes in daily life.

Focused Attention

As the name implies, Focused Attention entails focusing attention on a single object, thought, or physiological process. For example, some mindfulness programs begin by having you focus your attention on the inward and outward flow of your breath. The idea is to train your mind to focus more acutely during the practice, so that when you come out into activity, you have a greater ability to notice what is going on, to stay connected, and to be in the moment.

Focused Attention entails focusing attention on a single object, thought, or physiological process.

Open Monitoring

Open Monitoring addresses another aspect of being mindful, which is learning how to manage how stress colors our perception of the world. We have all experienced how we might be in the most beautiful place in the world, say watching a sunset over the Grand Canyon, but if we are anxious, depressed, or angry, our mood can totally ruin our experience. Our conditioning history, our stresses, our stuff distorts how we experience life and distracts us from being “mindful” of what is really going on.

Open Monitoring is a meditative practice that attempts to manage our stresses by training us not to respond to them emotionally. The practitioner, while sitting with eyes closed, monitors his stream of thoughts and practices a nonjudgmental attitude towards them. For example, if an angry thought arises, one attempts to stay calm and be neutral about it. Or one may think to oneself, “I am having these thoughts, but they are not myself.” Such techniques can be practiced in activity as well as with eyes closed, and they are helpful in managing stress.

Open Monitoring is a meditative practice that attempts to manage our stresses by training us not to respond to them emotionally.

TM = Automatic Self-Transcending

The Transcendental Meditation technique takes a different approach to dealing with stresses, which is to eliminate their physiological basis instead of trying to manage them. With the effortless use of the mantra, the mind automatically settles into a physiological condition of deep rest, inner wakefulness, and enhanced brain coherence. This state of restful alertness is different from waking, dreaming, or sleep states of consciousness.

TM takes a different approach to dealing with stresses, which is to eliminate their physiological basis instead of trying to manage them.

TM is effortless because it works on the basis of the natural tendency of the mind to automatically be drawn to a field of greater charm. What does that mean? It is a common experience that our minds are automatically drawn to things that are more interesting, more beautiful, and more full of love and harmony. Quieter, subtler levels of mental activity are inherently more charming because they’re more settled and harmonious; hence, during TM the mind is automatically drawn inward. For these reasons, the practice of TM is characterized as Automatic Self-Transcending.

The Wisdom of the Body

Stresses, which limit our enjoyment of life, are due to some excessive pressure of experience, which creates structural or functional abnormalities in the nervous system. The stuff we carry around with us is composed of these stresses stored in the body. It would be virtually impossible to track down and eliminate each stress one by one, even if we knew how to do that—which we don’t.

Fortunately, the wisdom of the body can do it. In scientific terminology, this wisdom is composed of the innumerable interlocking homeostatic feedback loops that are constantly detecting and correcting imbalances in the body, such as in our blood pressure, temperature, blood pH, insulin levels, tissue damage, hormone levels, and much more.

Stresses, which limit our enjoyment of life, are due to some excessive pressure of experience, which creates structural or functional abnormalities in the nervous system.

As imbalances are detected, the body’s self-correcting mechanisms automatically and unconsciously come into play to rebalance the system to a more ideal state of homeostasis and health. When we get sick, whatever else the doctor tells us to do, almost universally she says “get more rest,” because rest allows these self-healing mechanisms to do their work most efficiently.

How Restful Alertness Helps Eliminate Stress

With TM we are adding (not substituting) periods of restful alertness to the ordinary cycles of waking, sleeping, and dreaming. Restful alertness has a different physiology from these three states, and it supplements the body’s healing power. Because of its unique neurophysiological characteristics, the state of restful alertness constitutes a fourth major state of consciousness—Transcendental Consciousness. The increased EEG coherence during TM practice indicates a high degree of connectivity and coordination among the cortical areas of the brain, which appears to facilitate the body’s self-healing process.

This enhanced health effect has been demonstrated by health insurance statistics. One study of 2,000 TM meditators over a five-year period showed that they had lower rates of hospitalization in every category of disease, 50 percent lower on average.2 The number of days they spent in the hospital were 30 percent less, an indication that TM practice accelerates normal healing processes.

Three Types of Meditation. Focused Attention and Open Monitoring are placed at the top of the chart because they operate at the active level of the mind and require some degree of mental effort. The Transcendental Meditation technique allows the mind to effortlessly and spontaneously transcend to quieter, subtler levels to experience the silent mind, the fourth state of consciousness, Transcendental Consciousness.

Psychological research shows that TM practice is the most effective meditation or relaxation technique for reducing anxiety,3,4 and other studies show it reduces depression 5 and hostility.6 Other research shows that TM participants perceive the world in a more positive light,7 and that TM is the most effective means of gaining self-actualization.8

These findings suggest that TM practice helps people effortlessly achieve the goal of Open Monitoring, which is to manage one’s emotional response. It also helps people effortlessly achieve the goal of Focused Attention, as indicated by such changes as faster reactions, increased intelligence, creativity, and academic performance.9

Findings suggest that TM practice helps people effortlessly achieve the goals of both Open Monitoring and Focused Attention.

Effortless Effects in Activity

The ultimate goal of all meditation techniques is to help us enjoy the world in a fresh way, to live each precious moment fully, unimpeded by the distorting influences of stress. Different meditation approaches work by different mechanisms and are effective in different ways.

Focused Attention and Open Monitoring are cognitive techniques, which allow one to practice the goals that one wants to attain. If you want to become more focused, practice focusing. If you want to manage your stresses, practice doing so with Open Monitoring.

Mindfulness techniques, which involve both of these approaches, require differing degrees of mental control. As a result, many people find them to be rather strenuous.

In contrast, the TM technique effortlessly creates a state of restful alertness. This state allows your body to repair the consequences of stress from the inside, so that you come out of meditation into activity feeling more rested, with a higher level of brain integration. This allows you to be more focused and more free from stress, and to spontaneously live life with greater alertness and enjoyment each day.

[…] Three Types of Meditation. Focused Attention (concentration) and Open Monitoring (contemplation) are placed at the top of the chart because they operate at the active level of the mind and require some degree of mental effort. The Transcendental Meditation technique allows the mind to effortlessly and spontaneously transcend to quieter, subtler levels to experience the silent mind, the fourth state of consciousness, Transcendental Consciousness. For more about the research on different kinds of meditation, see Dr. David Orme-Johnson’s “How Does TM Differ from Mindfulness?” […]

All these practices maintain the subject -object split between observer/meditator and the object of awareness: external object, sensarion, breath, thought, mantra. Whilst this division exists there is a contraction and therefore stress in awareness. Once the practice finishes and the time-out from activity is left behind the stress of being a separate individual up against the world will gradually return. Until the subject becomes the focus of awareness and is inquired into all these practices are limited.

Thank you, Tony, you bring out a great point. The TM technique is a simple effortless process that allows the active, conscious mind to settled into the simplest state of awareness, pure consciousness, which is beyond the duality of the subject/object experience. Your question also provides an opportunity to explain the practice of TM in terms of the tripartite division of knower, object of knowing, and the processes of knowing that connect them. In all phases of waking state of consciousness these are separate: the observer is observing the object of observation. I see the tree. I am aware of my thoughts. I smell the rose.

I am not quite sure what you mean by “there is a contraction and therefore stress in awareness.” There is a stress in the sense that the nature of the observer as unbounded, pure consciousness remains hidden from itself in the waking state. The observed, in a sense, covers up the observer. In one of Maharishi’s analogies, it is like a movie projecting on a screen. The movie, the object of awareness, dances on the screen, and the awareness of the screen is lost. Similarly, the knower that is our own unbounded Self is not aware of itself because attention is always projecting outward to the object.

The key is to have a technique that allows the attention to settle back onto itself until the observer experiences the observer as the object of its observation. Does this sound like Marx brothers’ double talk? Actually, it is super simple. During TM what happens is that the mind (the observer) experiences the object of awareness, the mantra, in spontaneously finer states, until the mind transcends all mental activity and the observer experiences the silent state of his or her pure consciousness, the Self. In that unified state of knower, knowing, and known, the mind finds fulfillment, self-realization, and all anxiety stemming from duality is assuaged. To use another analogy, when the waves on the ocean settle down completely, what remains is the flat glassy surface of the unbounded ocean. Like that, when thought waves settle down, unbounded awareness is experienced.

Transcending is the state of “time out from activity,” as Tony observes, and when we return to activity after meditation, we are again back to the division of observer, observation, and observed. It is the only practical thing to do, to get on with our lives. But there is one difference, which is that the experience of Transcendental Consciousness during TM habituates the physiology to maintain it more and more in activity, which is the basis for the growth of enlightenment. We will be going into what enlightenment is, how it develops, and the scientific research on it in my next article in Enjoy TM News.

Other meditation techniques maintain object-referral awareness of some physiological process, perceptual object, the steam of consciousness, etc. Transcending is not their goal, and the role of repeated transcending to develop enlightenment is not part of their theoretical framework.

One caution: It is important to remember that holding onto an idea of the Self during activity is not the same as spontaneously living the reality of the experience. Practices that try to intellectually maintain Self-awareness during activity may break the all-important mind-body coordination, which could lead to failures and accidents. If the baseball is flying at you and you are half watching it and half thinking, “I am one, I am the self, etc.,” you will not be able to hit it the ball, and may even get bonked on the head.

Mindfulness is similar and different to TM practice, but the description given here is lacking. It could be said that thought monitoring is done in either type of practice, simply because thoughts, images, memories, emotions arise and are dismissed systematically in either practice. What is left out is that during a mindfulness program such as vipassana, one returns to a system of observation that could easily be compared to mantra meditation. Is the mind “thinking” when on the mantra? Supposedly not. Is the mind thinking while observing body sensations? Supposedly not. Is the mind thinking while observing the breath, sounds, anything else? Depends on one’s level of consciousness. Also, as in TM, it is the effect of practice, not the practice itself, which results in the ability to manage stress.

This is a good question, because it takes the discussion to a deeper level. Verbal descriptions about what happens during different meditation techniques can sound similar and thus be confusing. Objective neurophysiological research helps clarify how meditations differ. Research on the DMN, fMRI, and EEG power and coherence indicate that the TM technique alone is effortless, that is, does not involve monitoring or cognitive control. It enlivens a state of restful alertness and increased brain integration that is not produced by other meditation techniques. Here are the details.

1. DMN. As is described in the research by Fred Travis, Ph.D., and Niyazi Parim, M.A., that is introduced in this issue of Enjoy TM News, it is well-known in neuroscience that mental activity that demands focus and cognitive control decreases activity in the Default Mode Network (DMN). All meditation techniques except TM decrease DMN activity. This indicates that other meditations require a greater degree of cognitive control and effort than TM does. (1) https://enjoytmnews.org/new-research-effortlessness-key-tm-technique-132/

Travis and Parim also report that the brain changes seen during TM distinguish it from ordinary resting with eyes closed. Changes during TM indicate less internal speech and reduced supervisory oversight of mental activity compared to ordinary resting. This coincides with the experience that TM is easy and effortless.

(Also see the video by Maharishi on the key to effortlessness in this issue

https://enjoytmnews.org/the-blissful-nature-of-the-tm-technique/)

2. fMRI. Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging shows that different meditation techniques produce different patterns of blood flow in the brain, indicating that they differ in the mental processes they require. During mindfulness, blood flow increases in the anterior cingulate gyrus, which indicates attention is being directed on monitoring some task. This accords with the DMN results showing that mindfulness decreases DMN activity, indicating it requires mental control. The data indicate that there is no monitoring of thoughts during TM in the same sense that mindfulness requires monitoring, because the areas of the brain controlling monitoring are not active during TM. Instead, during TM there is decreased blood flow to the brain stem and pons, which corresponds to increased rest (e.g., lower rates of breathing and heart rate, etc.), and there is increased frontal blood flow, which corresponds to increased inner awareness—hence, another perspective on restful alertness.

3. EEG power. Different meditation techniques have different EEG signatures, which relate to what people practicing those technique experience subjectively. Focused Attention meditations create gamma (20-40 Hz), which is a known correlate of tasks that require focused attention. Open monitoring (like Vipassana) results in theta EEG (4-7 Hz), which is known to occur during monitoring inner thought processes. The EEG signature of TM is alpha1 (8-9 Hz), the index of restful alertness.(2) From the EEG we can construct a scale of degree of cognitive control that different meditation techniques require: Focused Attention requires the most, Open Monitoring a moderate amount, and TM requires the least or no amount.

4. EEG coherence. EEG coherence is a measure of the synchronization of the EEG coming from different parts of the brain. A comprehensive review of EEG changes during different meditation techniques cited twelves studies on TM showing it increases inter-hemispheric and intra-hemispheric alpha coherence.(3) Not one study on mindfulness or Vipassana showed this effect. The relevance of alpha coherence is that it reflects the long-range integration of brain areas needed for perception, muscle movements, memory, and creativity (4-6), all of which TM improves. Moreover, in the experience of Transcendental Consciousness during TM, when the mind transcends thought and experiences pure consciousness, the breath rate becomes all but suspended and the EEG shows increased coherence between all areas of the brain across all EEG frequencies.(7) No other meditation technique has ever been demonstrated to produce transcending and these effects.

You make a good point that the ability to manage stress is the effect of the practice, not the practice itself. But as Dr. John Shear has pointed out, the mechanisms of how TM and other techniques accomplish stress reduction are quite different.(8) During mindfulness the meditator practices the specific skill of having a non-judgmental attitude towards stress so that hopefully this habit will carry over into activity. During TM there is no practice of any specific skill, but rather the effortless experience of transcending all mental activity to enliven the state of restful alertness, which spontaneously increases brain integration in activity.

Moreover, the health, cognitive, and behavioral benefits of mindfulness are not the same as TM. There are now hundreds of studies on mindfulness, and what they show is that mindfulness does not reduce blood pressure, for example (9, 10), whereas TM does. (11, 12) There are no good studies showing that mindfulness increases creativity and intelligence as TM does (13), or any long-term studies showing mindfulness reduces prison recidivism or health care expenditures as TM does (14, 15), or long-term studies showing it has the same effect on ego development and wisdom as TM (16). Mindfulness has consistently been shown to have only half the effect of TM on reducing anxiety and PTSD symptoms.(17-20) These data further highlight that different meditation techniques are quite different.

In conclusion, whatever the apparent similarities in the verbal descriptions of different meditation techniques, the neurophysiological data indicate that they are quite distinct, indicating that the mental processes that they require must also be distinct. Research on the DMN, fMRI, and EEG power and coherence indicate that the TM technique is effortless, does not involve monitoring or cognitive control, and enlivens a state of restful alertness and increased brain integration that is not produced by other meditation techniques.

References

1. Travis F, Parim N. Default Mode Network activation and Transcendental Meditation practice: Focused Attention or Automatic Self-Transcending? Brain and Cognition. 2017;111:86-94.

2. Travis FT, Shear J. Focused attention, open monitoring and automatic self-transcending: Categories to organize meditations from Vedic, Buddhist and Chinese traditions. Consciousness and Cognition. 2010;19(4):1110-8.

3. Cahn BR, Polich J. Meditation states and traits: EEG, ERP, and neuroimaging studies. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132(2):180-211.

4. Orme-Johnson DW, Haynes CT. EEG phase coherence, pure consciousness, creativity and TM-Sidhi experiences. International Journal of Neuroscience. 1981;13:211-7.

5. Palva S, Palva JM. New vistas for α-frequency band oscillations. Trends in Neurosciences. 2007;30(4):150-8.

6. Sauseng P, Klimesch W. What does phase information of oscillatory brain activity tell us about cognitive processes? Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2008;32(5):1001-13.

7. Badawi K, Wallace RK, Orme-Johnson DW, Rouzeré A-M. Electrophysiologic characteristics of respiratory suspension periods occurring during the practice of the Transcendental Meditation program. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1984;46(3):267-76.

8. Shear J. State-enlivening and practice-makes-perfect approaches to meditation. Biofeedback. 2011;39(2):51-5.

9. Blom K, Baker B, How M, Dai M, Irvine J, Abbey S, et al. Hypertension analysis of stress reduction using mindfulness meditation and yoga: Results from the Harmony Randomized Control trial. American Journal of Hypertension. 2014;27(1):122-9.

10. Brook RD, Appel LJ, Rubenfire M, Ogedegbe G, Bisognano JD, Elliott WJ, et al. Beyond medications and diet: Alternative approaches to lowering blood pressure : A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension: Journal of the American Heart Association. 2013;61(6):1360-83.

11. Rainforth MV, Schneider RH, Nidich SI, Gaylord-King C, Salerno JW, Anderson JW. Stress reduction programs in patients with elevated blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Current Hypertension Report. 2007;9(6):520-8.

12. Anderson JW, Liu CH, Kryscio RJ. Blood pressure response to Transcendental Meditation: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Hypertension. 2008;21(3):310-6.

13. So KT, Orme-Johnson DW. Three randomized experiments on the holistic longitudinal effects of the Transcendental Meditation technique on cognition. Intelligence. 2001;29(5):419-40.

14. Rainforth MV, Bleick C, Alexander CN, Cavanaugh KL. The Transcendental Meditation program and criminal recidivism in Folsom State Prisoners: A 15-year follow-up study. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 2003;36:181-204.

15. Herron RE, Hillis SL, Mandarino JV, Orme-Johnson DW, Walton KG. The impact of the Transcendental Meditation program on government payments to physicians in Quebec. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1996;10(3):208-16.

16. Chandler H, Alexander C, Heaton D, Grant J. Transcendental Meditation and postconventional self-development: a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality. 2005;17(1):93-122.

17. Orme-Johnson DW, Barnes VA. Effects of the Transcendental Meditation technique on trait anxiety: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2013;20(5):330-41.

18. Sedlmeier P, Eberth J, Schwarz M, Zimmermann D, Haarig F. The psychological effects of meditation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2012;138(6):1139-71.

19. Brooks JS, Scarano T. Transcendental Meditation and the treatment of post-Vietnam adjustment. Journal of Counseling and Development. 1985;64:212-5.

20. Rees B, Travis F, Shapiro D, Chant R. Reduction in post traumatic stress symptoms in Congolese refugees practicing Transcendental Meditation. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2013;26:295-8.

You explain it very beautifully . I am doing TM from the last 30 years and I would like to know if there is any electronic device which can measure the level of changes during tm session? I mean for a common man who can use it at his home.

Thank you. There are some devices under development to measure changes during meditation, but none are generally available at this time. One is an inexpensive attachment to a laptop that can measure the number of spontaneous skin resistance responses (SSRR) as an index of stress. When we get stressed, for example by a loud noise, part of the stress response is increased sweatiness of the palms, which is easily measured. Spontaneous SRRs are ones that occur even when one is sitting quietly in a stress-free environment. These stress responses are in response to something that is going on inside of the person, maybe a stressful thought or the normalizing of some physiological process. SSRR is an index of how much stress a person has.

My first research study on TM in 1973 found that SSRRs are decreased during TM and are lower in meditators than non-meditators. People practicing TM had measurably less stress in them. I was excited that there was a way to measure this! I called it autonomic stability, and now, 43 years later, there are many studies showing that TM increases autonomic stability, for example in college students as well in war veterans with PTSD.

Importantly, the degree of our autonomic stability influences how we react to stresses encountered in daily life. I found that people with greater autonomic stability recovered faster from stressors. Also, research by the Air Force found that candidates for becoming pilots who had greater autonomic stability could withstand more G-forces in a centrifuge accelerator before blacking out. They were stronger. And other studies showed it was associated with greater ego strength, the ability to stay centered and maintain a sense of self and be effective in challenging situations. So autonomic stability is a good thing and we can measure it. The challenge is to make a valid, simple, turn-key operation instrument that does not require a skilled technician to operate.

There are also efforts afoot to make a simple EEG machine that could be used to measure changes during meditation, but the technical problems are even more challenging with EEG because the signals are very low voltage and dealing with artifacts is tricky.

There are EEG systems on the market that are sold to measure meditation. They basically distinguish periods of alpha activity (8-12 Hz), which indicates relaxation, from beta (12.5 to 30 Hz), which indicates focused attention. They are fun to play with, but don’t really capture what happens in TM. The main indicator of TM is coherence or correlation between the alpha 1 EEG (8-9 Hz) from different brain areas, primarily frontal areas. This means that the different areas of the brain are working together harmoniously, like a well-rehearsed orchestra. So far, this has remained in the laboratory.

Caveats

Now here are some caveats to the enterprise of creating devices to measure meditation. TM is an inward process, and you don’t want any kind of biofeedback signals telling you that you are deep in meditation because that would pull your attention in an outward direction and be disruptive to the meditation. It would probably give you a headache.

Another caveat is that TM is a process, not a single state. It is not as if there is a golden goal that would indicate a correct meditation. For example, if one is tired, one could fall asleep and that would be a perfectly correct meditation for that time. Absolutely the best way to find out if you are meditating correctly is to be checked by a qualified TM teacher. It might be theoretically possible to train Siri to do it. I just asked her, and she said “I don’t see an App for checking my meditation. You could try searching the App store.” Well, I have done that, and as mentioned above, these devices have limited usefulness.

Better to retain the human element and the trained TM teacher in the equation.

Thanks for your question.

Why do I get a headache if I don’t meditate and the only thing that makes it go away is to meditate? I learned TM in 1973.

Your experience that your headaches go away when you meditate suggests that the headaches are stress-related, because TM’s physiological effects are in the opposite direction of the stress response. Straining, tension, and stress in activity are common causes of headaches, and clinical experience has shown that TM reduces frequent headaches as well as migraines.

If you are not meditating regularly and have headaches outside of meditation, try meditating regularly. This may take care of the problem. Many meditators report that regular TM practice over time has been effective in reducing and sometimes eliminating headaches altogether.

If you are meditating regularly and have headaches in activity, be sure that you have the right balance of rest and activity in your life. If you are straining, overworking, or not getting enough rest in general, this can cause more stress leading to headaches and other imbalances.

I also recommend that you make an appointment with your or a TM Teacher to have your meditation checked. There is no cost, and this is a great way to ensure that you are meditating correctly and gaining maximum from your practice.

If these recommendations don’t work and you still have headaches in activity, I would suggest that it may be a medical condition and you should consult a doctor.