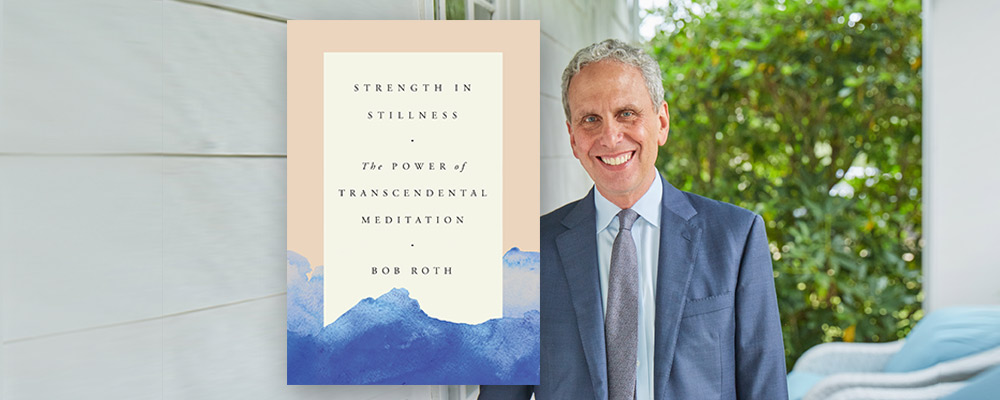

The following is an excerpt from the final chapter of Bob Roth’s Strength in Stillness: The Power of Transcendental Meditation, which is titled “My Own Story.”

I grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area in the 1950s and 1960s, inheriting a passion for education from my schoolteacher mother and a deep respect for science and a healthy dose of skepticism from my radiologist father.

I was accepted into the University of California at Berkeley in October 1968. My plan was to eventually attend UC Berkeley’s law school, become a lawyer, and then become a U.S. senator, like Bobby Kennedy. I thought the way to improve people’s lives would be through politics and changing public policy.

Then, Bobby Kennedy was assassinated. Coming just two months after the slaying of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the feelings of this idealistic 17-year-old were almost too much to bear.

“Tumult on Steroids”

That first year at Berkeley was very tough. The university was in a state of constant upheaval, with war protests devolving into riots. There were helicopters spewing tear gas overhead and tactical police and National Guard tanks parked outside my dorm.

I thought the way to improve people’s lives would be through politics and changing public policy.

I remember walking home from a physics class on College Avenue and hearing a thunder of feet behind me. I turned around, and there were 30 Oakland tactical police waving billy clubs, chasing me. I had done nothing wrong. Luckily, I ran much faster than they did.

I was 18, and the first year of college is supposed to be tumultuous anyway. But with all the unrest on campus, mine was tumult on steroids. For the first time in my privileged young life, I had an inkling of what it was like to feel unsettled, disconnected, and unsafe. Even small things started to worry me, and outsized reactions to small events just built on each other.

“Lighting a Fire”

The brutally divisive 1968 presidential race between Richard Nixon and Vice President Hubert Humphrey left me disillusioned with pursuing politics as a career path. Inspired by my mother’s love of teaching and memories of working with a young African American kid named Kenny and his mom, I decided that I would pursue a doctorate in education instead.

My plan was to specialize in developing educational curricula to help underserved kids not just learn the basics, such as algebra, but also to acquire social and emotional tools to survive and, hopefully, rise above their challenging circumstances.

I fervently agreed with the Irish poet William Butler Yeats, who wrote, “Education is not about filling the pail; it is about lighting a fire.”

While I worked toward that goal, I had a stint to earn some extra cash at a Swensen’s ice cream parlor on Durant Avenue. It was just north of Telegraph Avenue, where street demonstrations against the Vietnam War were almost a daily occurrence. And it was at Swensen’s that I met a co-worker named Peter Stevens.

“Education is not about filling the pail; it is about lighting a fire.” —William Butler Yeats

“A Get-It-Done Kind of Guy” Takes a Leap

I’d worked with Peter about six months when, one night around 10 o’clock, I took a break from studying and went into Swensen’s to get some ice cream. I knew Peter was working the late shift, but he was nowhere in sight.

“Where’s Peter?” I asked another worker.

“Oh, he’s in the back meditating,” she said.

“What?”

Just the word meditating struck me like an electric shock. It had such a bizarre connotation and really wasn’t even in my vocabulary.

But when he walked out to the front of the store, there he was, just Peter, but a little brighter than usual, smiling a little more, with a little more serenity on his kind face. I took notice.

I asked what he was doing, and he told me he practiced the Transcendental Meditation® (TM®) technique. Of course, I had heard about it because the press had made such a big deal of the Beatles going off to India to study TM with Maharishi in early 1968.

Sitting in one place with my eyes closed meditating had never been very appealing to me. I saw myself as a doer; a get-it-done kind of a guy. I wanted to change the world, and that required action. I also thought maybe it was a philosophy or religion, and I just wasn’t into that.

But when he walked out, there he was, just Peter, but a little brighter than usual, smiling a little more, with a little more serenity on his kind face. I took notice.

On the other hand, I was pretty stressed out, and I did respect Peter a lot. I found myself curious. I asked him to tell me more. I decided to take a leap, and attend what was billed as an introductory lecture.

“You Don’t Have to Believe in Gravity”

A woman in her late 20s gave the talk, and she ran through the basics of the practice and its benefits. At the end, she asked if there were questions. I raised my hand and asked, “This all sounds good, but how much do I have to believe for it to work?”

The woman nodded amiably. Then she held up a piece of chalk in her right hand. She waited a moment, and then dropped the chalk into her outstretched left hand below.

“You don’t have to believe in gravity for this chalk to fall,” she said. “Like that, you don’t have to believe in anything to practice TM.” In fact, she said, I could be 100 percent skeptical, and the technique would work just fine.

“You don’t have to believe in anything to practice TM.” —TM teacher

That clicked with me. I liked that I could be a skeptic and didn’t have to “believe” in Transcendental Meditation for the technique to work.

The only firm conviction I had about it, in fact, was that I was going to be the one person who would be unable to meditate. She assured me that everyone has this nagging suspicion, and yes, anyone can learn.

“Both Unique and as Familiar and Natural as Could Be”

Two days later, on the sunny Saturday morning of June 28, 1969, I returned to the TM Center to start the course. Sylvia Schmidt was my teacher. She was in her early 30s, a soft-spoken academic. I walked with her into the small instruction room on the second floor.

“Okay, I’m here,” I thought to myself as I settled into a comfortable chair to her left.

As Sylvia led me through the beginning steps of instruction, I felt my mind and body sinking into a state of deep relaxation.

Within seconds of my first experience meditating, I felt this wave of physiological peace come over me. The tension in my neck, shoulders, and stomach muscles was the first to go—and my racing mind settled down.

Now, remember, I was a tightly wound, skeptical 18-year-old kid. And yet within seconds of my first experience meditating, I felt this wave of physiological peace come over me. The tension in my neck, shoulders, and stomach muscles was the first to go—and my racing mind settled down.

Yet I was fully aware, fully awake. It was both unique and as familiar and natural as could be.

Once the meditation was over, I remember thinking to myself, “This is something. It’s not just my imagination or visualizing; this is really something.” One of my next thoughts was, “I would like to teach this to kids.”

“A Shared Desire to Do Something Good for the World”

Flash-forward 35 years. I love teaching people to meditate, all sorts of people, but working with kids has always had a special place in my life. Because, going back to my roots, if you want to create a better world, it has to begin with young people.

I found someone of like mind in 2004. He was the great filmmaker, painter, musician, woodworker, sculptor, and longtime TM practitioner, David Lynch. We became fast friends, like brothers, first working together on a project to build a large TM Center in Los Angeles.

Several months later, I spoke with David and Dr. John Hagelin, a Harvard-trained quantum physicist, who heads up the TM organization in the United States and is president of Maharishi University of Management®. I told them of my long-standing desire to bring TM to young people.

“Let’s start a foundation,” I said.

“Good idea,” David and John agreed.

“We should put it in your name, David,” I replied.

“All right,” he said.

“Can I send out a press release to announce the David Lynch FoundationSM?”

“Sure,” he said, most likely thinking not much would come of it.

David’s foundation was born on July 21, 2005. The press release was picked up by the major wire services, and within a few days, news stories of the formation of the David Lynch Foundation began appearing in thousands of newspapers all over the world.

It was really as simple as that. No great forethought. No five-year business plan. No money, even. Just a genuine shared desire to do something good for the world.

And so much good has come of it.

► Order your copy of Strength in Stillness: The Power of Transcendental Meditation

Thank you for all you have shared, and all you have given to the world. You are a quietly powerful force for good, and your work has changed so many lives for the better. I look forward to reading your book.

Started TM in 1970. After Won 5 Powerlifting World Titles 20 World Records And Numerous Hall of Fame Inductions!!!