Dr. Norman Rosenthal is a world-renowned psychiatrist and author whose research on seasonal affective disorder (SAD) has helped millions of people. His book Transcendence: Healing and Transformation through Transcendental Meditation was a New York Times bestseller, and his latest book is Super Mind: How to Boost Performance and Live a Richer and Happier Life through Transcendental Meditation. He is Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at Georgetown University Medical School. The Poetry of Transcendence is from Dr. Rosenthal’s new website on the healing power of poetry, Poetry Rx.

Tran·scend: To go beyond or rise above a limit, or be greater than something ordinary. —Oxford Dictionary

There is something beyond our mind which abides in silence within our mind. It is the supreme mystery beyond thought. —Maitri Upanishad

I have often wondered about the word “transcendence,” about what it means to go beyond or rise above a limit, as the Oxford Dictionary definition suggests. But it was only when I took up the Transcendental Meditation® (TM®) technique over a decade ago that I gave the matter serious thought. When it came to writing a book about the technique and the state of Transcendental Consciousness that is its hallmark feature, the title Transcendence seemed like an obvious choice.

William James, who is known as the father of psychology, wrote in his classic work Varieties of Religious Experience:

Our normal waking consciousness… is but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, parted from it by the filmiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness entirely different.

He goes on to say that people may live their whole lives without being aware of these other states of consciousness, but if they apply “the requisite stimulus,” then at a touch, these other states of consciousness become entirely accessible. The state of transcendence is, to borrow William James’ expression, one such “special type of consciousness.”

I have often wondered about the word “transcendence”… But it was only when I took up the Transcendental Meditation technique over a decade ago that I gave the matter serious thought.

Transcendental Consciousness

According to the Vedic tradition, from which the TM technique comes, transcendence is the fourth state of consciousness, the first three being sleeping, waking, and dreaming. I must confess that when I first heard about this so-called fourth state of consciousness, I was skeptical of its existence.

There are hundreds of scientific studies on the TM technique

Since the early 1970s, however, hundreds of scientific studies on the TM technique have shown the specific physiological and brain EEG changes experienced during TM practice, a state of restful alertness unlike waking, dreaming, or sleep. These made me curious to learn more.

But it was only after I started to practice Transcendental Meditation and effortlessly experienced the state of transcendence myself, just as it has been described in the literature, that I could personally confirm its existence.

For those of you who have yet to begin the TM technique and experience transcendence, I do not expect you to take it on faith. Nevertheless, I hope this piece of writing will stimulate your curiosity to learn more. To find out about the TM technique and the scientific research on it, visit TM.org.

Those of us who practice TM are familiar with transcendence. For us, what James calls “the requisite stimulus” is the easy, effortless mental technique of Transcendental Meditation, which we learn from a certified TM teacher.

Over the centuries, however, philosophers, writers, athletes, and others have spontaneously experienced this state of transcendence in other ways, as beautifully depicted by Craig Pearson in his book The Supreme Awakening: Experiences of Enlightenment Throughout Time—and How You Can Cultivate Them.

Those of us who practice TM are familiar with transcendence. For us, what James calls “the requisite stimulus” is the easy, effortless mental technique of Transcendental Meditation.

The Power of Poetry

If transcendence is, as in the above quote from the Upanishads, something that abides in silence within our mind and is such a mystery, how can it be described? Moreover, why even try to find words to convey such a mysterious state?

Henry David Thoreau, author of Walden, and a photo of Walden Pond in Massachusetts

I put this question to Bob Roth, director and CEO of the David Lynch FoundationSM, which brings the TM technique to at-risk populations. He quoted Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the Founder of the TM program, as saying that transcendence is such a blissful state that hearing descriptions of it would encourage those who are not yet meditating to learn.

Let us then consider what poetry, perhaps the most beautiful form of verbal communication, can offer those who wish to better understand the state of mind that the American author Henry David Thoreau described in his Journals as “like a still lake of purest crystal” where “without an effort our depths are revealed to ourselves.”

If transcendence is, as in the above quote from the Upanishads, something that abides in silence within our mind and is such a mystery, how can it be described?

Wordsworth: A Transcendent Poet

If ever there was a transcendent poet, it is William Wordsworth, whose responses to nature transcended what he observed in the world around him to encompass the emotions and physical changes these observations evoked in him. Wordsworth transformed these responses into immortal poems, which continue to delight and, I would suggest, heal.

The famous ruins of Tintern Abbey in England

A famous example of this effect can be seen in the poem commonly known as “Tintern Abbey,” an abbreviation for its full title, “Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey, On Revisiting the Banks of the Wye during a Tour. July 13, 1798.”

Wordsworth had visited the same site five years earlier when he was 23 and in a troubled state. In the poem he recounts revisiting the scene, now more mature as a person and a poet.

After describing the rolling waters of mountain springs, the cliffs, trees, and hedge rows, he goes on to document the way they make him feel physically and emotionally. Here is an excerpt from this remarkable poem:

…These beauteous forms,

Through a long absence, have not been to me

As is a landscape to a blind man’s eye:

But oft, in lonely rooms, and ‘mid the din

Of towns and cities, I have owed to them,

In hours of weariness, sensations sweet,

Felt in the blood, and felt along the heart;

And passing even into my purer mind

With tranquil restoration:—feelings too

Of unremembered pleasure: such, perhaps,

As have no slight or trivial influence

On that best portion of a good man’s life,

His little, nameless, unremembered, acts

Of kindness and of love. Nor less, I trust,

To them I may have owed another gift,

Of aspect more sublime; that blessed mood,

In which the burthen of the mystery,

In which the heavy and the weary weight

Of all this unintelligible world,

Is lightened:—that serene and blessed mood,

In which the affections gently lead us on,—

Until, the breath of this corporeal frame

And even the motion of our human blood

Almost suspended, we are laid asleep

In body, and become a living soul:

While with an eye made quiet by the power

Of harmony, and the deep power of joy,

We see into the life of things.

“Almost suspended, we are laid asleep

In body, and become a living soul… ” —Wordsworth

“Tranquil Restoration”

As you can see, Wordsworth expresses gratitude for what he owes to the memory of “these beauteous forms.” He accurately describes a certain aspect of transcendence:

…sensations sweet,

Felt in the blood, and felt along the heart;

And passing even into my purer mind

With tranquil restoration

These words remind me of how one TM practitioner once described transcendence to me, as something sweet, almost like the feeling a bee might have on sucking nectar from a flower. Wordsworth’s feelings of “tranquility and restoration” are also reminiscent of experiences that commonly arise from our practice of Transcendental Meditation.

Wordsworth then describes a cluster of associations with this state of tranquility: a mixture of joy and gratitude. When we practice the TM technique we often experience similar feelings of bliss, as a result of the mind effortlessly settling down into a state of pure consciousness.

Wordsworth’s feelings of “tranquility and restoration” are also reminiscent of experiences that commonly arise from our practice of Transcendental Meditation.

“That Blessed Mood”

The poet’s focus then shifts, moving from the mind to the body, which, as TM meditators know from their first meditations, is powerfully affected during states of transcendence:

…that blessed mood,

In which the burthen of the mystery,

In which the heavy and the weary weight

Of all this unintelligible world,

Is lightened

How often we feel a sense of physical lightness or calmness come over us during and after we emerge from a state of transcendence! The effects of this state on the body continue in ways familiar to any TM practitioner, such as the slowing of the breath, which scientists have documented to be a cardinal physical correlate of transcendence.

Then the poet’s imagination soars as he suggests that even the motion of the blood becomes suspended. According to him, so profound is this slowing down that we are “laid asleep / in body” even as we “become a living soul”—a beautiful description of the calm, restful alertness of transcendence, the fourth state of consciousness.

In the final words of this memorable stanza, the poet observes the insight that sometimes emerges from transcendence, the ability to “see into the life of things,” to see something anew in all its vibrant vitality.

We are “laid asleep / in body” even as we “become a living soul”—a beautiful description of the calm alertness of transcendence, the fourth state of consciousness… a state of restful alertness.

So, here is what we can say about “Tintern Abbey” and the light it sheds on the state of transcendence:

1. Wordsworth describes a state of consciousness that resembles transcendence both with regard to physical and mental attributes: feelings of the breath and body slowing down; and blissful calm during the experience, as well as associated with the lively insight that can arise afterwards—the ability to “see into the life of things.”

2. Whereas for Wordsworth the “requisite stimulus” for transcendence is the presence of natural beauty, TM uses a simple mental technique to bring about effortless transcending.

3. Wordsworth’s description of both his surroundings and the feelings they evoke within him have the power to heal by eliciting similar responses in the reader.

Varieties of Transcendence

As TM meditators know, every meditation session is different. Although the elements described in “Tintern Abbey” capture many aspects of transcendence, some TM practitioners might describe their transcendent experiences very differently, as might different writers.

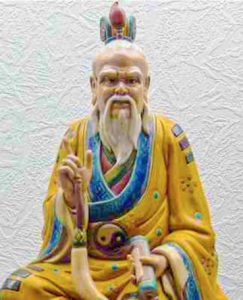

Lao-Tzu, author of the Tao Te Ching

Here is a poetic description of transcendence from the Tao Te Ching of Lao-Tzu, beautifully translated by Jonathan Star. This is not a description of the technique of transcending but the state of Transcendental Consciousness itself:

Become totally empty

Quiet the restlessness of the mind

Only then will you witness everything

unfolding from emptiness

See all things flourish and dance

in endless variation

And once again merge back into perfect

Emptiness—

On a book tour for Transcendence, I was delighted to be accompanied by my friend David Lynch, who was promoting his book Catching the Big Fish, which is about Transcendental Meditation and creativity. When the subject of transcendence came up, I would emphasize how much I enjoyed the calm serenity I experienced from my TM practice. David took issue with me about that. “I don’t want calm serenity,” he exclaimed on one occasion, “I want to splash around in pools of bliss.”

Wordsworth’s Daffodils and the Expansion of Consciousness

After I wrote my book Transcendence, with its focus on the growth of consciousness beyond the common states of sleeping, waking, and dreaming, I thought I had said everything worth saying about the effects of practicing the Transcendental Meditation technique. After all, I had dealt fully with the many benefits of TM, resulting largely from transcendence and its effects on relieving stress, that ubiquitous toxin of our frenetic modern lives.

But as I continued to meditate and shared my experiences with fellow meditators, I realized that there was much more to say. My consciousness continued to expand, with astonishing results. These observations led me to my second book on the TM program—Super Mind: How to Boost Performance and Live a Richer and Happier Life through Transcendental Meditation.

In Cosmic Consciousness, the state of Transcendental Consciousness is not only experienced during TM practice but along with waking, dreaming, and sleep

The Vedic tradition outlines a progression of consciousness beyond transcendence—that calm yet alert state that occurs during TM practice—in which the meditator begins to experience similar expansions of consciousness during regular daily life.

This is called the growth of Cosmic Consciousness, in which the state of Transcendental Consciousness is experienced at all times, even along with waking, dreaming, and sleep states.

As this progresses further, Refined Cosmic Consciousness appears, a state during which the world is perceived in fine-grained detail, as though illuminated by an inner radiance.

It is these next two states that we see in evidence in one of Wordsworth’s most famous poems, “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud.” In a 1995 BBC poll, this poem was rated as the United Kingdom’s fifth most favorite. It was inspired by a walk Wordsworth took with his sister Dorothy through the Lake District, a gorgeous part of England:

I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud

I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o’er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

Continuous as the stars that shine

And twinkle on the milky way,

They stretched in never-ending line

Along the margin of a bay:

Ten thousand saw I at a glance,

Tossing their heads in sprightly dance.

The waves beside them danced; but they

Out-did the sparkling waves in glee:

A poet could not but be gay,

In such a jocund company:

I gazed—and gazed—but little thought

What wealth the show to me had brought:

For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude;

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

At the very start of the poem, we find Wordsworth in a state that sounds like Cosmic Consciousness. Even as he is experiencing something like transcendence—which he represents as floating high above the ground like a cloud—he is also awake and active.

It is in this state of mind that he sees the mass of daffodils, which he describes in such gorgeous detail that they must surely be imprinted on the minds of millions who learned the poem in school. There is such a sense of profusion about the daffodils that even a single glance reveals ten thousand. But a finite number is insufficient to describe their massive expanse, which invites comparison to the stars in the milky way. They are never-ending.

At the same time, Wordsworth experiences in the daffodils an inner vitality reminiscent of his transcendent state of mind in “Tintern Abbey,” which enabled him to “see into the life of things.” This state of mind makes the daffodils seem like a crowd of fellow creatures, fluttering and dancing. He imbues them with human qualities. The sparkling waves cannot compete with them, at least with regard to their glee that is so contagious that “A poet could not but be gay, / In such a jocund company.”

“A host, of golden daffodils… Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.” —William Wordsworth

The poet is transfixed by the wonder of the sight, but as with “Tintern Abbey,” little does he realize the riches that this natural wonder will continue to yield. Later, when “In vacant or in pensive mood,” the daffodils will “flash upon that inward eye / Which is the bliss of solitude.” Once again, it sounds as though the poet is entering a state of transcendence, triggered by the recollection of natural beauty. He concludes with one of the most memorable couplets in all of poetry.

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

Wordsworth wrote “I wandered lonely as a cloud” in 1804, six years after “Tintern Abbey.” It is tempting to speculate that the capacity for transcendence that infused “Tintern Abbey” continued to grow. This expanded consciousness began to accompany Wordsworth’s daily waking state and enabled him to see the natural wonders around him, both with regard to their beauty and their inner life—even when they were just a memory.

“A State of Transcendent Wonder”

Another great poet who developed the capacity for Transcendental Consciousness is Alfred Lord Tennyson, as described in William James’ Varieties of Religious Experience. Here is Tennyson’s description of the state of transcendence that he spontaneously stumbled upon:

… a kind of waking trance—this for lack of a better word—I have frequently had, quite up from boyhood, when I have been all alone… All at once, as it were out of the intensity of the consciousness of individuality, the individuality itself seemed to dissolve and fade away into boundless being, and this not a confused state but the clearest, the surest of the surest… utterly beyond words—where death was an almost laughable impossibility, the loss of personality (if so it were) seeming no extinction, but the only true life… I am ashamed of my feeble description. Have I not said the state is utterly beyond words? … There is no delusion in the matter! It is no nebulous ecstasy, but a state of transcendent wonder, associated with absolute clearness of mind.

Learn more about the healing power of poetry at Dr. Rosenthal’s new website, Poetry Rx ►

There is a modern poet (and meditator), Rafael Jesus Gonazalez that you may be aware of? He writes lovely poetry in English and Spanish. His 1978 Book “The Maker of Games”opens with a quote from Maharishi (in Spanish) His Poem “Windsong for Prince Henry’s Daughter” even alludes to TM (in a poetic way).

It is interesting to know about poetry. The poetic mind is a mind, which looks at events and objects with a touch of spirituality and mostly seeing the beauty of Nature and Creation. The human being is nothing but a bundle of thoughts and the greatness of mind is nothing but seeing the thoughts of one by himself and go beyond the thoughts. The mind, which has seen beyond an ordinary mind, and from that mind flows the thoughts and beauty in a poetic form.