This excerpt has been adapted from Dr. Craig Pearson’s popular collection The Supreme Awakening: Experiences of Enlightenment throughout Time—And How You Can Cultivate Them, which is now available as an ebook for Kindle.

We have all experienced in our practice of Transcendental Meditation® (TM®) how the mind settles down to deeper levels of inner calm and quiet. This is called “transcending.” It may be a vague or hazy experience, or sometimes it can be very clear: for a brief moment or longer, the mind slips into that state of profound silence. There is no mantra, no thought—just inner wakefulness.

When we emerge back into a more active mind we may think: “What was that? Everything seemed to fade away, and there was nothing but silence.”

Craig Pearson’s The Supreme Awakening is now available as an ebook on Kindle.

This is an experience of the transcendent, which is universally available to every human being. Throughout history, great men and women have described exalted periods of extraordinary wakefulness, freedom, and bliss—as different from our ordinary waking state as waking is from dreaming.

The Supreme Awakening offers a rich collection of these experiences. It shows how ordinary men and women today are enjoying the same kinds of sublime moments described by Laozi, Plato, Rumi, St. Teresa of Avila, Emerson, Emily Dickinson, Black Elk, Einstein, the Buddha, Wordsworth, Thoreau, and many others, simply by practicing the effortless technique of TM.

Walt Whitman’s transcendental experiences enabled him to produce some of America’s greatest poetry, expressing a vision of the inner glory of life and extending an invitation for everyone to join him there. His work also offers an opportunity for greater understanding of higher states of consciousness as described by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, Founder of the TM program. Whitman gives voice to the inexpressible experience of transcendence and Cosmic Consciousness, or enlightenment.

Whitman’s “Song of Myself”

Whitman (1819–1892) left school at age 11 and worked at a variety of trades—he was a printer, a teacher, a newspaper writer and editor, a stationer, and a real estate speculator. One never would have guessed he was destined to become America’s seer.

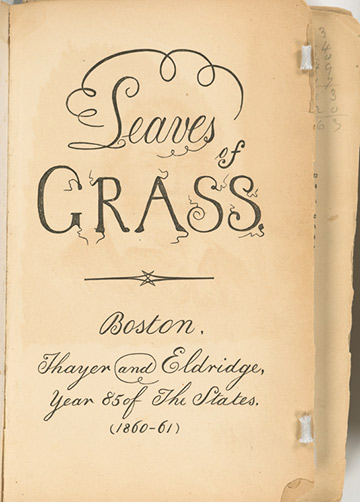

Leaves of Grass (Boston: Thayer and Eldridge, year 85 of the States, 1860) (New York Public Library)

In his early 30s, he began to have experiences that transformed him. In 1855, when he was 36, he published his collection of poems Leaves of Grass.

The poems seemed so radical in form and content that he became a revolutionary figure in American literature. In fact, he was initially acclaimed more as a prophet of democracy and of the “common man” in the Western world than as a poet.

His aim, he states in the book’s preface, is to “wellnigh express the inexpressible.” At the beginning of “Song of Myself” he sings, “I celebrate myself.”

But the self he celebrates is not the ordinary self we usually experience. This self is far more expanded and transcendental.

“Mightier Center of the True, the Good, the Loving”

In the following lines, from Whitman’s poem “Passage to India,” he eulogizes this transcendental field of life:

O Thou transcendent,

Nameless, the fibre and the breath,

Light of the light, shedding forth universes, thou center of them,

Thou mightier center of the true, the good, the loving,

Thou moral, spiritual fountain—affection’s source—thou reservoir,

(O pensive soul of me—O thirst unsatisfied—waitest not there?

Waitest not haply for us somewhere there the Comrade perfect?)

Thou pulse—thou motive of the stars, suns, systems,

That, circling, move in order, safe, harmonious,

Athwart the shapeless vastnesses of space,

How should I think, how breathe a single breath, how speak, if, out of myself,

I could not launch, to those, superior universes?1

These beautiful words hardly need a comment. Whitman speaks directly to the transcendent, the source and center of universes, the center of truth, goodness, and love. He declares at the end that everything he does, everything he is, depends on his ability to transcend, to move “out of myself” to that superior state.

“The Me in the Centre”

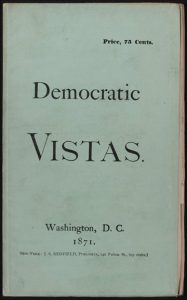

In Whitman’s prose work Democratic Vistas, he describes the kind of experience he enjoys:

Walt Whitman, Democratic Vistas, Washington, DC: J.S. Redfield, 1871 (Rare Book & Special Collections Division, Library of Congress)

“There is, in sanest hours, a consciousness, a thought that rises, independent, lifted out from all else, calm, like the stars, shining eternal. This is the thought of identity—yours for you, whoever you are, as mine for me. Miracle of miracles, beyond statement, most spiritual and vaguest of earth’s dreams, yet hardest basic fact, and only entrance to all facts. In such devout hours, in the midst of the significant wonders of heaven and earth, (significant only because of the Me in the centre), creeds, conventions, fall away and become of no account before this simple idea. Under the luminousness of real vision, it alone takes possession, takes value. Like the shadowy dwarf in the fable, once liberated and look’d upon, it expands over the whole earth, and spreads to the roof of heaven.”2

Whitman is clearly describing an experience of transcendence. The experience, he tells us, is “independent, lifted out from all else.” It is unbounded—“it expands over the whole earth, and spreads to the roof of heaven.” It is highly abstract, the “most spiritual and vaguest of earth’s dreams.” Yet it is the ultimate reality, Whitman asserts, the “hardest basic fact, and only entrance to all facts.”

The great work of Maharishi was to bring to light a simple, natural, and effortless procedure—the TM technique—for experiencing the fourth state of consciousness, Transcendental Consciousness.

Whitman never said anything about how he was able to have this experience. Like so many people through history, it seems to have been a matter of good luck. The great work of Maharishi was to bring to light, from the world’s most ancient continuous tradition of knowledge, a simple, natural, and effortless procedure—the Transcendental Meditation technique—for experiencing the fourth state of consciousness, Transcendental Consciousness.

“Reach the Divine Levels, and Commune with the Unutterable”

In this state, the mind has settled inward. Moving beyond all perceptions, thoughts, and feelings, one experiences consciousness by itself, consciousness knowing itself alone. This is pure consciousness, unbounded and fully awake within itself. Simultaneously, the body becomes deeply restful while brain functioning becomes integrated, suggesting the total brain is awake. This, Maharishi explains, is the true Self.

Whitman goes on to describe the transcendental quality of this unique experience:

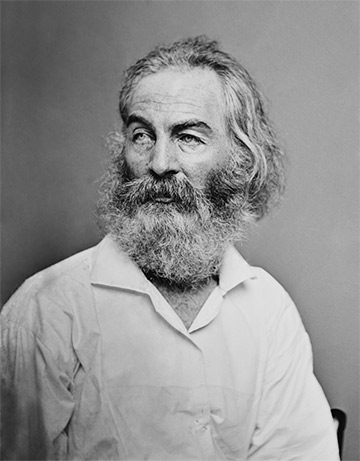

Walt Whitman, c. 1855-1865, by photographer Matthew Brady (1822-1896) (Library of Congress, Brady-Handy Photograph Collection, via Wikimedia Commons)

“Only in the perfect uncontamination and solitariness of individuality…. Only here, and on such terms, the meditation, the devout ecstasy, the soaring flight. Only here, communion with the mysteries…. The soul emerges, and all statements, churches, sermons, melt away like vapors. Alone, and silent thought and awe, and aspiration—and then the interior consciousness, like a hitherto unseen inscription, in magic ink, beams out its wondrous lines to the sense. Bibles may convey, and priests expound, but it is exclusively for the noiseless operation of one’s isolated self, to enter the pure ether of veneration, reach the divine levels, and commune with the unutterable.”3

Whitman makes clear that this “interior consciousness” is the most important thing we can experience in life. In comparison, he says, all intellectual beliefs, all creeds and conventions, “become of no account.” “All statements” about the nature of reality “melt away like vapors.” Direct experience alone matters, he says—and full direct experience takes place exclusively through “the noiseless operation of one’s isolated self.”

The central, inner reality of life, Maharishi observes, is pure consciousness, the Self. Throughout this passage, Whitman seeks to convey precisely this knowledge—and the fact that one can experience it directly.

“Apart from the Pulling and Hauling Stands What I Am”

When one first learns the TM technique, one typically experiences the unbounded awareness of the fourth state only for brief moments, at the deepest points of meditation. But in time, with repeated, twice-daily experience, one’s mind becomes so familiar with this unbounded pure awareness that one begins to maintain the experience of it for longer periods—first during meditation and then outside meditation as well.

Gradually, this experience of Transcendental Consciousness becomes permanent, forming an underlying continuum that coexists with waking, dreaming, and sleeping. These three states continue to come and go as before, but pure consciousness remains constant. The awareness of the Self is never extinguished.

This is a fifth state of consciousness, altogether different from waking, dreaming, sleeping, and Transcendental Consciousness. Maharishi termed this fifth state “Cosmic Consciousness,” because it is all-inclusive, all-encompassing.

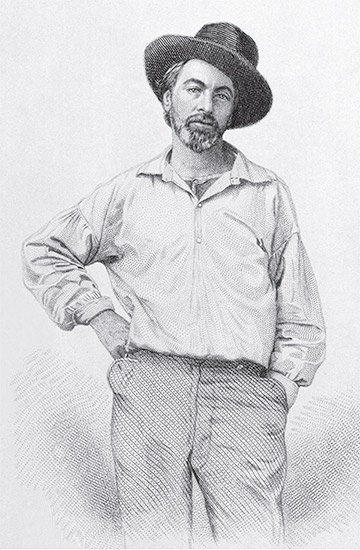

Steel engraving of Walt Whitman, published in the 1855 edition of Leaves of Grass, by Samuel Hollyer (1826-1919) of a daguerreotype by Gabriel Harrison (1818-1902) (Morgan Library & Museum, via Wikimedia Commons)

Whitman describes experiences reminiscent of Cosmic Consciousness in his poetry. These momentary or partial views may not be the state itself, but they give us a glimpse of the indescribable.

In Whitman’s most famous poem, “Song of Myself,” the poet inventories various elements in his life, then announces that these are not the true “Me myself / Apart from the pulling and hauling stands what I am.”

In the following passage, “What I am,” he declares, stands apart from all this, unified and restful. He lives “both in and out of the game,” suggesting the dual experience in Cosmic Consciousness of the self as ever-changing and the Self as a never-changing, transcendental witness.

In the last two lines, he honors both sides of himself: “my Soul” (his unbounded, witnessing Self) and “the other I am” (his waking-state personality). Both have their important roles to play:

Trippers and askers surround me,

People I meet, the effect upon me of my early life or the ward and city I live in, or the nation,

The latest dates, discoveries, inventions, societies, authors old and new,

My dinner, dress, associates, looks, compliments, dues;

. . .

These come to me days and nights and go from me again,

But they are not the Me myself.

Apart from the pulling and hauling stands what I am,

Stands amused, complacent, compassionating, idle, unitary,

Looks down, is erect, or bends an arm on an impalpable certain rest,

Looking with sidecurved head curious what will come next,

Both in and out of the game and watching and wondering at it.

Backward I see in my own days where I sweated through fog with linguists and contenders,

I have no mockings or arguments, I witness and wait.

I believe in you, my Soul—the other I am must not abase itself to you,

And you must not be abased to the other.4

Whitman describes experiences reminiscent of Cosmic Consciousness in his poetry… they give us a glimpse of the indescribable.

A Vision of the Growth of Cosmic Consciousness

The experience of growing Cosmic Consciousness is natural, normal, and enjoyable. As your nervous system becomes progressively free of stress, you spontaneously express more of your inner potential. You grow in creativity and intelligence, alertness and evenness, happiness, and fulfillment.

Today the experience of Transcendental Consciousness and the gradual development of Cosmic Consciousness is no longer just a matter of good luck. Now, anyone can, in Whitman’s words, “reach the interior consciousness.” Now, anyone can “reach the divine levels, and commune with the unutterable.”

To learn more about higher states of consciousness, visit EnjoyTM.org ►

References

1. Walt Whitman, “Passage to India,” Leaves of Grass (Philadelphia: David McKay, 1891), 315.

2. Walt Whitman, “Democratic Vistas,” Walt Whitman: Complete Poetry and Collected Prose, ed. Justin Kaplan (New York: J.S. Redfield, 1871), 41.

3. “Democratic Vistas,” in Walt Whitman, 47.

4. Walt Whitman, “Song of Myself,” Leaves of Grass (Philadelphia: David McKay, 1892), 31.

Whitman’s works are also available online at The Walt Whitman Archive ►

Craig Pearson, Ph.D., is the author of The Supreme Awakening: Experiences of Enlightenment throughout Time—And How You Can Cultivate Them, and Vice President of Academic Affairs at Maharishi University of Management in Fairfield, Iowa.

To order a copy of The Supreme Awakening, click here ►

The Supreme Awakening is now available on Amazon for Kindle ►

Thank you so much for Walt Whitman post! Also for Trending Video, Role Family Life in Developing Consciousness. Am watching on email sent by Newport Beach. Unfortunately doesn’t play beyond a few minutes. Any way I can get it? Would like to send to my family. Thanks again, for all! JGD

Thank you Gail! I’m so glad you enjoyed reading this wonderful article about Walt Whitman, who’s one of my all-time favorite poets.

I’m sorry you had trouble viewing all of the Trending Video. I just tested it again, and it played all the way through. Have you tried it recently? Perhaps the connection was slow so your browser was having trouble loading it completely. You can try again linking either from the Trending Video banner on the homepage, or going directly to the video on EnjoyTM.org. I hope that helps, so you can share with your family!